Learning and Knowledge

Category: Biology

Learning is a process that depends on experience and leads to long-term changes in behavior potential. Behavior potential designates the possible behavior of an individual, not actual behavior. The main assumption behind all learning psychology is that the effects of the environment, conditioning, reinforcement, etc. provide psychologists with the best information from which to understand human behavior.

As opposed to short term changes in behavior potential (caused e.g. by fatigue) learning implies long term changes. As opposed to long term changes caused by aging and development, learning implies changes related directly to experience. Experience determined your perception and therefor your behavior/actions on certain things. If someone experiences something there preconceived personsal biases and stereotypes determines the way that they will experience and perceive the event.

Learning theories try to better understand how the learning process works. Major research traditions are behaviorism, cognitivism and self-regulated learning. Media psychology is a newer addition among the learning theories because there is so much technology now included in the various types of learning experiences. Neurosciences have provided important insights into learning, too, even when using much simpler organisms than humans (aplysia). Distance learning, eLearning, online learning, blended learning, and media psychology are emerging dimensions of the

Learning theories are conceptual frameworks that describe how information is absorbed, processed, and retained during learning. Cognitive, emotional, and environmental influences, as well as prior experience, all play a part in how understanding, or a world view, is acquired or changed, and knowledge and skills retained.

Behaviorists look at learning as an aspect of conditioning and will advocate a system of rewards and targets in education. Educators who embrace cognitive theory believe that the definition of learning as a change in behavior is too narrow and prefer to study the learner rather than the environment, and in particular the complexities of human memory. Humanists emphasize the importance of self-knowledge and relationships in the learning process. Those who advocate constructivism believe that a learner's ability to learn relies to a large extent on what he already knows and understands, and that the acquisition of knowledge should be an individually tailored process of construction.

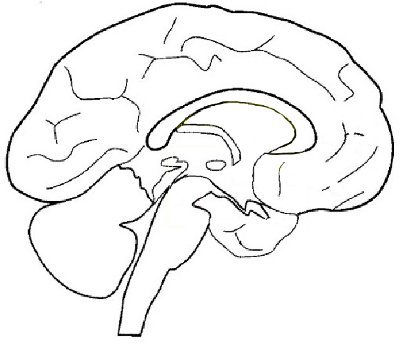

Outside the realm of educational psychology, techniques to directly observe the functioning of the brain during the learning process, such as event-related potential and functional magnetic resonance imaging, are used in educational neuroscience. As of 2012, such studies are beginning to support a theory of multiple intelligences, where learning is seen as the interaction between dozens of different functional areas in the brain, each with their own individual strengths and weaknesses in any particular human learner.

In psychology, cognitivism is a theoretical framework for understanding the mind that gained credence in the 1950s. The movement was a response to behaviorism, which cognitivists said neglected to explain cognition. Cognitive psychology derived its name from the Latin cognoscere, referring to knowing and information, thus cognitive psychology is an information processing psychology derived in part from earlier traditions of the investigation of thought and problem solving. Behaviorists acknowledged the existence of thinking, but identified it as a behavior. Cognitivists argued that the way people think impacts their behavior and therefore cannot be a behavior in and of itself. Cognitivists later argued that thinking is so essential to psychology that the study of thinking should become its own field.

History of learning

Socrates

Socrates (469-399 B.C.) introduced a method of learning that is now referred to as piloting. Piloting refers to arriving at answers through one's own power of reasoning. This was used when Socrates was teaching geometry to a young slave boy who knew math but nothing of geometry. He would ask this boy to solve a problem like finding the area of a square. When the boy would get the answer incorrect he would repeatedly question his reasoning by contradicting his logic. The notion that knowledge comes from within was inspired by Socrates and his experiments.

Plato

Many have interpreted Plato as stating—even having been the first to write—thatknowledge is justified true belief, an influential view that informed future developments in epistemology. This interpretation is partly based on a reading of the Theaetetus wherein Plato argues that knowledge is distinguished from mere true belief by the knower having an "account" of the object of her or his true belief (Theaetetus 201c-d). And this theory may again be seen in the Meno, where it is suggested that true belief can be raised to the level of knowledge if it is bound with an account as to the question of "why" the object of the true belief is so (Meno 97d-98a). Many years later, Edmund Gettier famously demonstrated the problems of the justified true belief account of knowledge. That the modern theory of justified true belief as knowledge which Gettier addresses is equivalent to Plato's is accepted by some scholars but rejected by others.

Aristotle

Like his teacher Plato, Aristotle's philosophy aims at the universal. Aristotle's ontology, however, finds the universal in particular things, which he calls the essence of things, while in Plato's ontology, the universal exists apart from particular things, and is related to them as their prototype or exemplar. For Aristotle, therefore, epistemology is based on the study of particular phenomena and rises to the knowledge of essences, while for Plato epistemology begins with knowledge of universal Forms (or ideas) and descends to knowledge of particular imitations of these. For Aristotle, "form" still refers to the unconditional basis ofphenomena but is "instantiated" in a particular substance (see Universals and particulars, below). In a certain sense, Aristotle's method is both inductive anddeductive, while Plato's is essentially deductive from a priori principles.

In Aristotle's terminology, "natural philosophy" is a branch of philosophy examining the phenomena of the natural world, and includes fields that would be regarded today as physics, biology and other natural sciences. In modern times, the scope of philosophy has become limited to more generic or abstract inquiries, such as ethics and metaphysics, in which logic plays a major role. Today's philosophy tends to exclude empirical study of the natural world by means of the scientific method. In contrast, Aristotle's philosophical endeavors encompassed virtually all facets of intellectual inquiry.

In the larger sense of the word, Aristotle makes philosophy coextensive with reasoning, which he also would describe as "science". Note, however, that his use of the term science carries a different meaning than that covered by the term "scientific method". For Aristotle, "all science (dianoia) is either practical, poetical or theoretical" (Metaphysics 1025b25). By practical science, he means ethics and politics; by poetical science, he means the study of poetry and the other fine arts; by theoretical science, he means physics,mathematics and metaphysics.

If logic (or "analytics") is regarded as a study preliminary to philosophy, the divisions of Aristotelian philosophy would consist of: (1) Logic; (2) Theoretical Philosophy, including Metaphysics, Physics and Mathematics; (3) Practical Philosophy and (4) Poetical Philosophy.

In the period between his two stays in Athens, between his times at the Academy and the Lyceum, Aristotle conducted most of the scientific thinking and research for which he is renowned today. In fact, most of Aristotle's life was devoted to the study of the objects of natural science. Aristotle's metaphysics contains observations on the nature of numbers but he made no original contributions to mathematics. He did, however, perform original research in the natural sciences, e.g., botany, zoology, physics, astronomy, chemistry, meteorology, and several other sciences.

Aristotle's writings on science are largely qualitative, as opposed to quantitative. Beginning in the 16th century, scientists began applying mathematics to the physical sciences, and Aristotle's work in this area was deemed hopelessly inadequate. His failings were largely due to the absence of concepts like mass, velocity, force and temperature. He had a conception of speed and temperature, but no quantitative understanding of them, which was partly due to the absence of basic experimental devices, like clocks and thermometers.

His writings provide an account of many scientific observations, a mixture of precocious accuracy and curious errors. For example, in his History of Animals he claimed that human males have more teeth than females. In a similar vein, John Philoponus, and later Galileo, showed by simple experiments that Aristotle's theory that a heavier object falls faster than a lighter object is incorrect.[23] On the other hand, Aristotle refuted Democritus's claim that the Milky Way was made up of "those stars which are shaded by the earth from the sun's rays," pointing out (correctly, even if such reasoning was bound to be dismissed for a long time) that, given "current astronomical demonstrations" that "the size of the sun is greater than that of the earth and the distance of the stars from the earth many times greater than that of the sun, then ... the sun shines on all the stars and the earth screens none of them."

In places, Aristotle goes too far in deriving 'laws of the universe' from simple observation and over-stretched reason. Today's scientific method assumes that such thinking without sufficient facts is ineffective, and that discerning the validity of one's hypothesis requires far more rigorous experimentation than that which Aristotle used to support his laws.

Aristotle also had some scientific blind spots. He posited a geocentric cosmologythat we may discern in selections of the Metaphysics, which was widely accepted up until the 16th century. From the 3rd century to the 16th century, the dominant view held that the Earth was the rotational center of the universe.

Since he was perhaps the philosopher most respected by European thinkers during and after the Renaissance, these thinkers often took Aristotle's erroneous positions as given, which held back science in this epoch. However, Aristotle's scientific shortcomings should not mislead one into forgetting his great advances in the many scientific fields. For instance, he founded logic as a formal science and created foundations to biology that were not superseded for two millennia. Moreover, he introduced the fundamental notion that nature is composed of things that change and that studying such changes can provide useful knowledge of underlying constants.

Back To Category Biology

Back To Category Biology